Last Updated on September 27, 2012 by Chicago Policy Review Staff

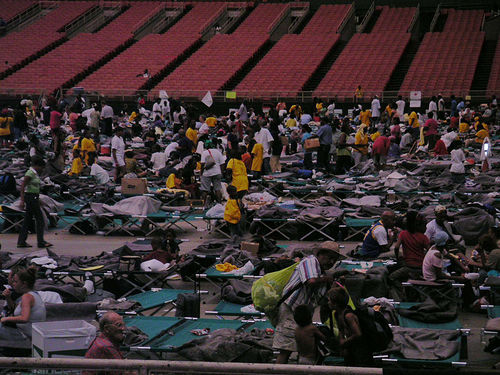

With the loss of over 1,800 lives and property damage estimated at $81 billion, Hurricane Katrina was the costliest natural disaster in the history of the United States, forcing more than one million Gulf Coast residents to evacuate their homes. In “Looking for Home after Katrina: Postdisaster Housing Policy and Low-Income Survivors,” Mueller, Bell, Chang, and Henneberger reflect on Hurricane Katrina and document the unique challenges faced by low-income survivors in rebuilding their lives following natural disasters.

For low-income survivors, the confusion and uncertainty surrounding Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) policies intensify their dependence on postdisaster assistance and hinder their ability to find work and attain greater independence in their daily lives. Post-Katrina, low-income survivors oftentimes received inadequate assistance, leaving them even more vulnerable than before the storm, particularly when faced with limited prospects for securing permanent housing elsewhere.Low-income survivors are more likely to have lived in informal settings—for example, with members of their extended family or with friends—before a disaster. The “shared household rule” that FEMA enforced post-Katrina limited assistance to one applicant per household, even if members of the household had been split up during evacuation. The authors recommend that this rule be revised to account for survivors who previously lived in these informal settings.

Homeowners also faced barriers to recovery, particularly when un- or under-insured, even with federal programs like HUD’s Road Home Program. Only 20 percent of Road Home recipients in New Orleans received support sufficient to cover repairs, with an average shortfall of $46,000 per household across the state of Louisiana. Low-income and African-American communities were disproportionately affected. Furthermore, the fear of defaulting on their mortgages pressured low-income homeowners to return to their homes even if repair resources and temporary housing were unavailable.

Those who lived in publicly subsidized housing before the disaster had the clearest path to permanent housing through established programs, yet struggled as a result of confusion about eligibility requirements and about emergency housing assistance.

The authors advocate for policymakers to consider the importance of pre-disaster income status to best meet the needs of disaster survivors. Indeed, prioritizing the needs of displaced, vulnerable populations and acknowledging suvivors’ right to return to their home community and be permanently housed would put U.S. policy in line with United Nations Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. The authors recommend that federal and local agencies collaborate more closely following a disaster, and also recommend that the Stafford Act be amended to allow the repair of rental housing to be an appropriate use of FEMA funding. The latter policy would be both more cost-effective than paying for survivors’ rent or trailers and also less disruptive than prolonged displacement with little prospect of return.